Time-travelling back to 2005: New J.K. Rowling interview material (Part 1)!

Jul 15, 2018

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Interviews, J.K. Rowling, JKR Interviews, JKRowling.com, News

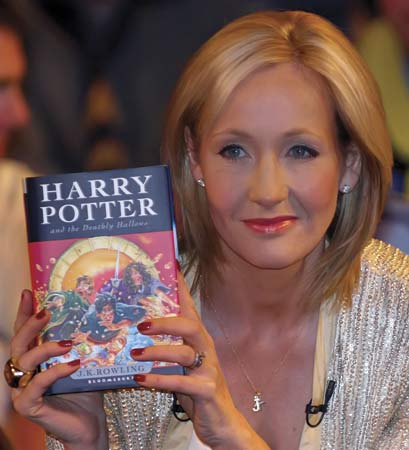

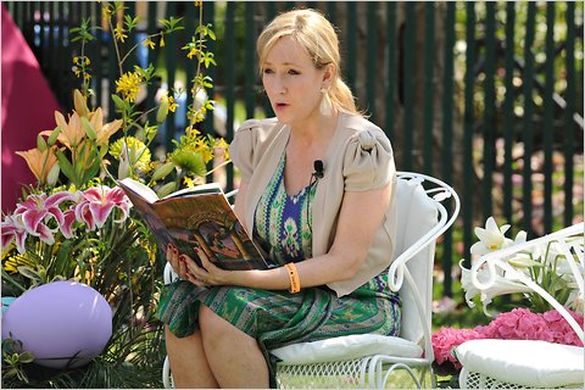

On July 17th 2005, the day after the publication of the Half-Blood Prince, Lev Grossman published a write up of his interview with J.K. Rowling in Time Magazine. On July 13th 2005 Grossman had an extensive, two-hour interview with Rowling but, as he has documented, only a small percentage of what Rowling said in that interview made it into print. What this means for us is that there is a mine of undiscovered gems which can take us time-travelling back to a moment when the ending of Harry Potter was still unknown. With immense kindness Lev Grossman shared the transcript of this interview with Dr Beatrice Groves, Research Fellow in Renaissance English at the University of Oxford and author of Literary Allusion In Harry Potter, who has produced a three-part write-up of the new material to celebrate the anniversary of Half Blood Prince:

This interview takes us back to a pre-Twitter time when Rowling still had a relatively private persona, and she was carefully ‘keeping the secrets’ while also teasing the reader with half-veiled access to the story’s future. What follows are some of my favourite insights from the unpublished parts of the 2005 interview; an interview given at a time when Rowling was happy to sit down for hours and just discuss Harry Potter.

Part 1: Responding to Readers

In an excellent in-depth analysis of Rowling’s public statements, Angua (in an essay available in the Leaky Lounge archives) has argued that they show a clear, if unspoken, desire to guide reader-response to her work. But, of course, this does not happen if what she says is not reported. In 2005 Rowling’s authorial interpretation had far more power than it does now, because the story wasn’t done yet. It wasn’t just that nobody else knew how the story ended, it was also that without the ending we didn’t yet know exactly what we did know meant. Grossman put this beautifully when he wrote in his review of Deathly Hallows how turning the last page of that novel made him eager to start the whole series again: ‘now that I know how the series ends, that knowledge propagates its way back through the series, casting everything that came before it in a different light and giving it a fresh new meaning.’ All that meaning was still locked in the future in 2005 and every interview a chance to glean from the author’s mind whatever crumbs she was willing to drop.

One of the things that happens when we return to this 2005 interview is that we find that Rowling did drop a number of hints – hints that never made it into print. After the publication of Deathly Hallows (a novel with the working title Harry Potter and the Elder Wand) Rowling spoke of how ‘I must admit, I always wondered why nobody ever asked me what Dumbledore’s wand was made of! And I couldn’t say that, even when asked “what do you wish you’d been asked…” because it would have sign-posted just how significant that wand would become!’ Strikingly, however, she dropped a major hint about this wand in 2005 – a hint which seems in hindsight like playing with fire! She told Grossman that ‘the source of Dumbledore’s power is very rarely investigated.’ The interviewer, understandably unaware of his ‘scoop,’ did not print this comment, so readers were not lead by Rowling’s comment to ponder whether there were any questions that they ought to be asking about Dumbledore’s wand….

But something else this interview shows is that Rowling is not only trying to guide the reader’s response through her interviews; in subtle ways she also acknowledges that she is responsive to their criticism.

Sirius’s Mirror

In more recent times Rowling has occasionally taken to Twitter to respond to readers shouting ‘plot-hole!’ On 11 February 2016 she posted in (mock?!) exasperation:

Along with "the Horcrux wasn't destroyed in CoS because Harry didn't die #PleaseNeverAskMeThatAgainPlease" https://t.co/ih4QwuQncI

— J.K. Rowling (@jk_rowling) February 11, 2016

Later that year she caused an unwitting Twitter ‘storm’ by changing her Twitter bio to ‘FAQ answers: 1) Because the Basilisk didn’t kill him 2) Next year, I hope 3) Yes 4) Wait and see 5) No, he isn’t 6) No, her really isn’t 7) Yes, I’m sure.’ (Incidentally, I suspect Rowling had in the back of the mind when writing this the moment in Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm when the heroine, Flora Poste, being asked the same question over and over, writes ‘I did. F. Poste’ on a leaf from her pocket-diary and pins it to the door of the kitchen where it can be seen by everyone.)

One FAQ Rowling has not addressed in public, however, is the issue of the plot-hole created in Phoenix when Harry (desperately needing to contact his godfather) does not think to use the mirror which Sirius has given him expressly for that purpose. This is a fan complaint which she did, however, respond to in this 2005 interview:

“…why doesn’t he use the mirror? Yeah, I’ve had that one a lot. Well, as you may have suspected, the mirror is not gone. The mirror is important. The mirror’s coming back. A lot of people felt frustrated about that, and I wanted to say that, um, people expect me to tie everything up neatly. But life isn’t like that. And I felt that Harry made this strong decision which he shouldn’t have gone back on. I’m not going to use this mirror, I will never use this mirror, I’m not going to lure Sirius out of hiding. That’s the mirror gone into my case, I’m forgetting about the mirror. Then he panics, when he thinks that Sirius is being tortured and yes, he’s forgotten about the mirror. I needed him to forget about the mirror plot-wise. I wanted him to have the mirror, I didn’t want him to use the mirror, so my excuse for that is, um, you know, that he made the resolution and then forgets, in his panic. I think that holds up. But I accept that a lot of people found that unsatisfying, and there may have been other ways to do that. Although I couldn’t think of another way, and I did try.”

This defence is quite playful in tone – unusually Rowling acts out the scenario from Harry’s point of view: ‘that’s the mirror gone into my case, I’m forgetting about the mirror.’ She defends herself at some length here, arguing that Harry’s mental block has psychological plausibility, as well as plot-necessity, going for it. But she also acknowledges that frustrated fans have a point. And she also drops a hint that the mirror is going to be making a plot-important reappearance…

Pink Witches, Blue Wizards

In this interview Grossman asked Rowling whether she perceived a parallel between the richer style and language of Phoenix and Harry’s maturation. Rowling had spoken in earlier interviews in a similar vein, suggesting that the structure of the series echoes Harry’s own development. She noted, for example, that the newly international focus of Goblet of Fire was ‘symbolic. Harry’s horizons are literally and metaphorically widening as he grows older.’ The influence of Harry’s own viewpoint on the nature of the series, therefore, appears to be something that Rowling formulated relatively early, and she responded enthusiastically to Grossman’s reading of a connection between form and content in Phoenix:

“I think you’re absolutely right. And I think I allowed myself to stretch out a bit with the language, just as I was stretching out in the sense that the world was unfurling.”

Rowling’s pleasing metaphor – ‘I was stretching out in the sense that the world was unfurling’ – is partly a reference to the increasing number of new magical locations that appear in Phoenix. This is the first novel in which Harry explores the wider magical world and she noted in this interview that the scenes in places such as the Ministry of Magic, St Mungo’s and Grimmauld Place were some of her favourite parts of Phoenix to write. But she also intends that ‘unfurling’ to have a more important meaning:

“Harry’s world is populated with many more interesting women as he ages, and that was deliberate. Although some haven’t really seen it that way. He was surrounded largely by men when he was eleven, because boys seek out boys… But as he gets older, he finds it easier to talk to and feel comfortable with women around him. So I put more women in.”

It is noticeable that Rowling turns a question about style into a question about gender. She suggests that the way in which the books unfold from Harry’s perspective – ‘Harry is the eyes on to the books in the sense that it is always Harry’s point of view’ – meaning that they are not sexist per se but instead echo what the author believes is the sexist perspective of a pre-teen boy.

Grossman is not asking about gender but Rowling reads the question this way because she wants to defend herself against accusations of sexism: ‘some haven’t really seen it that way.’ This phrase suggests that (despite Rowling’s avowed inattention to critical studies of her work) she was aware feminist critiques of the series such as Christine Schoefer’s ‘Harry Potter’s Girl Trouble’ (2000) and/or Elizabeth Heilman’s ‘Blue Wizards and Pink Witches’ (2003). The distance which Rowling jumps from the question in order to address issues of gender points up her desire to defend her work from the accusation that it is un-feminist.

Writing and Reading aloud

It is also possible that in this interview Rowling obliquely responds to stylistic critiques of her work. Among the most famous of these are Harold Bloom’s accusation that Potter is ‘heavy on cliché’ and ‘not well written;’ and Stephen King’s observation (in an otherwise positive review of Phoenix) that Rowling has ‘never met [an adverb] she didn’t like.’

In this interview she tells Grossman that she has read the entire of Phoenix aloud to her husband and daughter (she later contradicts this in the 2008 Adeel Amini interview by saying that Deathly Hallows is the only novel she has re-read ‘post-publication’ – suggesting perhaps that she read this to her family pre-publication):

“…in reading aloud, I think you pick up things you wouldn’t pick up just on reading, you know, in the normal way; so I found problems with my language, things that irritated me. Mannerisms that irritated me.”

It might be an interesting, given Rowling’s observation here of how reading aloud gave her a fresh perspective on her style, to see whether this ushered any stylistic change for the final two novels. It seems likely that she is once again obliquely responding to criticism here – recognising and to an extent accepting some of the stylistic critiques which had been levelled at her. One way of reading her admission of finding ‘problems with my language, things that irritated me. Mannerisms that irritated me’ is that Rowling has chosen to respond in Half-Blood Prince to the charges levelled against her style. She suggests that she will be reducing some of her stylistic mannerisms (such as overuse of adverbs) in the final two novels, but she is chary of imputing this change to an outside agency. She locates it instead to her own experience of reading Harry Potter in a way that is new to her, although highly familiar to millions of others.

It is also pleasing to hear that Rowling experienced reading Potter aloud to her family, like so many of her fans. Children’s literature remains uniquely connected with ancient, oral, traditions of storytelling for – unlike most modern writing – children’s stories are still spoken aloud. Harry Potter has been listened to by millions: read aloud by parents, friends, siblings and in audiobook form. Maria Tatar, a Harvard scholar of children’s literature, has spoken about how it was only when she listened to the audiobooks of Harry Potter that she finally understood their popularity: ‘all of a sudden, I got it—I could remember it, and I could visualize it. So much of it is dialogue. It’s not exploring minds. It’s conversations and actions that drive these books.’ This sense of reading aloud opening up something new about the book is echoed over and over by fans. As one writes: ‘I am reading the books aloud to my son these days, and though I’ve read them to myself an embarrassing number of times, I have not said all these phrases or names aloud before, and I’m really noticing the artistry with which she shapes names.’ Reading aloud brings a new perspective to the reader (as well as the listener) even when that reader is the author herself.

Rowling has spoken of how satisfying she finds it that her books are being read aloud: ‘there’s nothing more gratifying than to listen to people saying that entire families read the books together… They read one chapter together and then they gathered again to read the next one… A lot of families told me they did that and that is gratifying in so many levels. The books have become a social act.’ There is a deeply pleasing circularity to the fact that this social act was replicated, for Phoenix at least, within the Murray household.

Check back tomorrow for Part 2!

Thanks to Lev Grossman for giving permission for the honor of having this new J.K. Rowling content added to Leaky’s extensive archives, and to Dr Beatrice Groves (who you can find on Twitter, here) for three excellent write-ups of the new material! Beatrice previously guest-published an analysis of the History of Magic exhibition at The British Library, which you can find here.