“Harry Potter: A History of Magic” and Plant Lore, Part One: J.K. Rowling and Culpeper’s Complete Herbal

Oct 04, 2018

Art, Bloomsbury, Books, Exclusives, Fandom, Films, Fun, Interviews, J.K. Rowling, Jim Kay, News

Harry Potter: A History of Magic opens at the New York Historical Society tomorrow, with a guide narrated by Natalie Dormer, and will bring together all audiobook readers for the first time ever. Though the New York City exhibition will contain different elements (Brian Selznick’s 20th anniversary illustrations for Scholastic, for example), it’s sure to give the same profound revelations of the mythology, lore and history which inspired J.K. Rowling when writing Harry Potter, and ways in which we can see magic throughout Muggle history.

To celebrate the opening of the exhibition in New York (Leaky is attending a special preview today!) Dr Beatrice Groves – publisher of Literary Allusion In Harry Potter and Potter-expert who previously analysed the exhibition when it appeared in London – will take us through some of objects and themes found in the exhibition, and centred around plant lore in the Harry Potter series and beyond. This first section takes a look at J.K. Rowling’s use of Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (which she admitted to having several copies of!), how key plants in the wizarding world reflect the doctrine of signatures, and the significance of Mandrakes in the series:

The exhibition Harry Potter: A History of Magic showcases many beautiful medieval and early modern herbal texts in its Herbology section. The importance of traditional plant lore in Harry Potter, however, extends far beyond Professor Sprout’s greenhouses. Rowling notes in the documentary accompanying this exhibition how she loves to use ‘pre-existing myths, or ideas of fantastic creatures and so on was a way of giving texture to the [Wizarding] world.’ Plant lore – from the doctrine of signatures to the language of flowers – is a rich source for the historical ‘texture’ which gives such depth to Rowling’s imagined world.

My first post about the History of Magic Exhibition mentioned the way in which Rowling uses the language of flowers to plant clues in her names (something I’ll explore in more depth later in this blog-series). The evocatively named sisters Lily and Petunia, for example, play on the lily as a symbol of purity and petunias as associated with resentment; while there is a well-known and persuasive fan theory that Snape’s first words to Harry about the Potions ingredients asphodel and bitterest wormwood express his regret for Lily’s death.

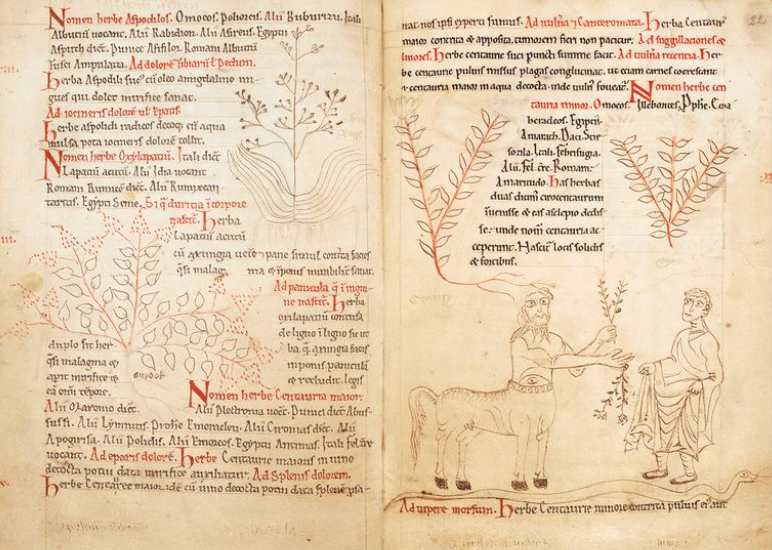

Another example of the way in which plant lore has deeper significance in Harry Potter is hinted at by another manuscript in the exhibition. A 12th century English herbal describes how the plant centaury can cure snakebite (it has a charming illustration of the centaur Chiron holding centaury while a snake slithers away from under his hooves:

(P.81, Harry Potter: A History of Magic – The Book of the Exhibition)

Centaury was named after the centaur Chiron who (according to Homer) passed on the knowledge of healing herbs to mankind (Iliad, Book 11.804-848). While other classical centaurs (like the centaurs of the Forbidden Forest) are generally antagonist to mankind, the generous and gifted Chiron became a tutor to heroes such as Achilles. Chiron, therefore, is the clear model for Firenze: the only Hogwarts centaur that thinks it worthwhile to tutor the hero. And the fact that the snake-bite curing centaury is named after Chiron gives this link a further, satisfying, twist. For just as Chiron is the centaur who protects humans from snakebite, so Firenze is the centaur who saves Harry from the snakey nightmare he meets him in the Forbidden Forest. (A creature that makes ‘a slithering sound’ (Philosopher’s Stone, Chap 15) – a clue to his snakey, Slytherin nature).

This blog series concentrates on the most important source for Rowling’s plant knowledge: Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (1652), a book prominently displayed in this exhibition.

(p.77 Harry Potter: A History of Magic – The Book of the Exhibition)

The exhibition catalogue notes both the extreme popularity of this work (it has been published in over one hundred editions, and was the first medical book to be published in North America) and also some tantalising details about its author: such as Culpeper’s trial, and acquittal, for practising witchcraft in 1642.

Uniquely we know that Rowling owns two quite different editions of Culpeper: in the exhibition display she notes that she has both ‘one a cheap edition I bought second-hand years ago and one beautiful version I was given by Bloomsbury.’ Rowling showed an interviewer that battered Wordsworth’s classics copy of Culpeper’s Complete Herbal in 2002 and spoke of it with great enthusiasm as a books she could ‘get lost in’:

“…this is so useful for me because I’m not a gardener – at all – and my knowledge of plants is not great and so I kind of collect, well I used to collect names of plants that sounded witchy and then I found this Culpeper’s Complete Herbal and it was the answer to my every prayer: [flicking through] Flaxweed, Toadflax, Fleawort, Goutwort, Gromel, knot-grass, Mugwort… just everything you could possibly, you know, so when I’m potioning I get lost in this for an hour. And the great thing is that it actually does tell you what they used to believe it did, so you can really use the right things in the potions you’re making up. So that was a very handy book to find.”

When Rowling first spoke about Culpeper in 2002 she said she delved into it so that she could use the ‘right’ ingredients in her fictional potions. Fifteen years later, in an interview given to promote the History of Magic exhibition, she says – slightly more circumspectly – that ‘even when I didn’t really use what [Culpeper was] saying, I found it inspirational, I found the way they talked about these plants inspirational.’

Culpepper leaves his fingerprints all over Hogwarts’s Potions classes but, as Rowling says, she often does not use him precisely, but creatively reworks his ideas. Take for example the way in which peppermint’s calming properties are kept but comically transformed. Culpepper notes that mint has a ‘binding, drying quality, and therefore… stays the hiccough, vomiting, and allays the choler.’ Culpepper’s celebration of mint’s ability to calm the body is transformed into an ability to mentally calm when it is added to the Elixir to Induce Euphoria: ‘a sprig of peppermint… unorthodox, but what a stroke of inspiration, Harry. Of course, that would tend to counterbalance the occasional side-effects of excessive singing and nose-tweaking’ (Half-Blood Prince, Chap 22).

Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (1652) sold like signed first editions of Magical Me when it came out, and it has (possibly uniquely for a non-religious work) remained in print ever since. One reason for this popularity was its cheapness. Rowling’s ‘cheap edition… bought second-hand’ is entirely in keeping with the affordability of the original book: roughly £1.30/ $1.70 in today’s money. In a highly unusual move Culpeper’s herbal advertised how cheap it was in its title: The English Physitian: or an Astrologo-Physical Discourse of the Vulgar Herbs of this Nation. Being a Compleat Method of Physick, whereby a man may preserve his Body in Health; or cure himself, being sick, for three pence charge, with such things only as grow in England, they being most fit for English Bodies.

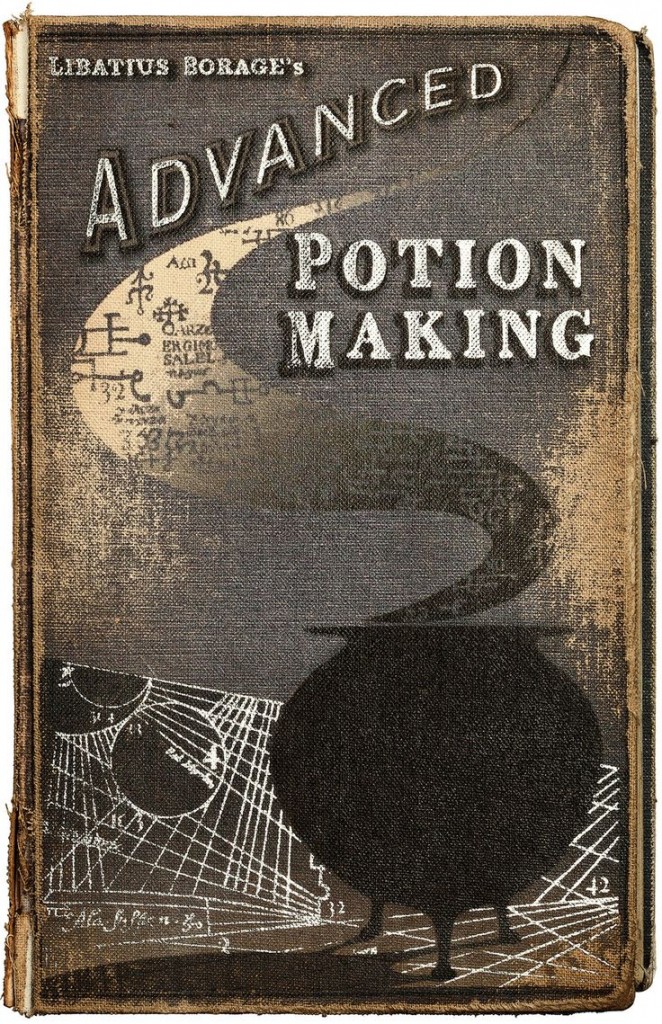

The main reason for Culpeper’s popularity was that his herbal was answering a real need for affordable healthcare at a time when few could afford doctors. His book cost only three pence and enabled the purchaser to make medicine from plants freely available in the hedgerows. There is also a certain nationalist pride in his advert of ‘Herbs of this Nation’ (or ‘local herbs for local people’) and his promise that, unlike other herbals stuffed with foreign plants, Culpeper’s herbal will detail only ‘such things only as grow in England, they being most fit for English Bodies.’ Harry Potter likewise takes place in an unapologetically British world (and, in an extension of this, Rowling famously insisted that the films must use only British actors). The author of Hogwarts’s Potion’s textbook Libatius Borage – the Wizarding version of Nicholas Culpeper – uses many native plants such as aconite, wormwood, knotgrass and wolfsbane and he himself is named after an old-fashioned British herb (its blue flowers, frozen in ice-cubes, perk up a pitcher of Pimm’s no end).

But Culpeper is also offering something a little more mystical here. His title promises an arcane ‘Astrologo-Physical Discourse.’ This word is Culpeper’s own invention (the Oxford English Dictionary has no entry for ‘Astrologo-Physical’) and it draws attention to a unique aspect of his work. Culpeper’s herbal, like all its rivals, gives a description of each plant and lists its medicinal values – but what is unique to Culpeper (along with its unusual affordability) is his classification of each plant according to his own astrological system. The beautiful, and beautifully named, viper’s bugloss, for example, ‘is a most gallant herb of the Sun’ and therefore is ‘most effectual to comfort the heart, and expel sadness, or causeless melancholy.’ Olav Thulesius suggests that this somewhat mystical side of Culpeper’s work was highly appealing and that his fame as an astrologer meant that his herbal might have been believed to offer ‘the ultimate mystery of the secrets of healing.’

(Photo: BBC – Photographer: Tom Hayward)

Rowling has spoken about how this side of Culpeper appealed to her:

‘It’s just the way they wrote about the plants and observed them and tied them planetary movements and so on. There’s such a poetry to it… Even when I didn’t really use what they were saying, I found it inspirational, I found the way they talked about these plants inspirational.’

This interconnected understanding of the natural world, held by many medieval herbalists and familiar in the present-day through Culpeper, lead to a belief in what is known as ‘the doctrine of signatures.’ This idea (which I will talk about further in my next blog) held that the shape of plants was part of the way in which God had ‘coded’ the natural world – from planetary motion to flower petals – with messages for mankind. According to the doctrine of signatures you can ‘read’ the medicinal value of a plant from its outward form: plants resemble the part of the body which they will cure.

The Doctrine of Signatures

The doctrine of signatures was widely accepted by traditional herbalists and is still legible today in many common plant names. If you come across a plant named ‘lungwort,’ ‘liverwort’ or ‘eyebright’ you can be confident that it was once believed to resemble that part of the body, and cure it too. The most famous literary example of this belief is given by Milton when the Archangel Michael ‘clears’ Adam’s eyesight using traditional herbal remedies. Adam’s visions of the future dominate the two final books of Paradise Lost (1667) and it is the angelic application of eyebright and rue which enables this astonishing visual and spiritual feat:

Michael from Adam’s eyes the film removed,

Which that false fruit that promised clearer sight

Had bred; then purged with euphrasy and rue

The visual nerve, for he had much to see. (Book 11, ll.412-15)

‘Euphrasy’ is the botanical name for eyebright, the flowers of which were said to resemble eyes, and to cure their ailments too.

Milton is, therefore, using a herb well-known from the doctrine of signatures to cure the eyes. (Poet-like, he is also punning: ‘euphrasy’ derives from the Greek for ‘cheerfulness,’ while the herb rue, of course, more familiarly means ‘sorrow, pity, repentance’ (see more on the symbolism of rue here). Milton’s herbs carry the deeper meaning that a tempering of sorrow and joy will put Adam in the right spiritual state to understand the angelic vision before him.

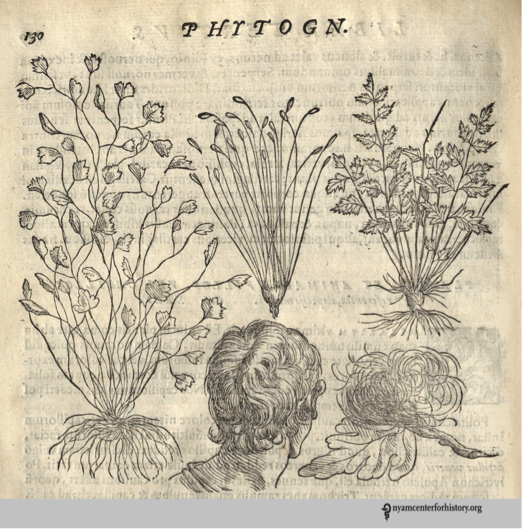

Culpeper was an enthusiastic supporter of the doctrine of signatures. He notes that lungwort is ‘spotted also with many small spots’ (resembling lung tissue) and ‘is of great use to physicians to help the diseases of the lungs;’ that liverwort ‘is a singular good herb for all diseases of the liver’ and that if eyebright were only used more often ‘it would half spoil the spectacle maker’s trade.’ Maidenhair, likewise, (the resemblance of which to a full head of hair is beautifully illustrated in this 1588 edition of Giambattista della Port’s Phytognomonica) is, according to Culpeper ‘effectual in all diseases of the head and falling of the recovering of hair.’

Mandrake or Mandragora: An unrecognised source for the Hand of Glory?

The synopsis of Philosopher’s Stone which Rowling submitted to prospective publishers (on display in the History of Magic exhibition) notes that Herbology was studied ‘out in the greenhouses where the mandrakes and wolfsbane are kept.’ Rowling has chosen two plants which will resonate within the series and they are plants that – like almost all the important plants in Harry Potter – fulfil the doctrine of signatures. In the Muggle world the wolfish looking wolfsbane was used to heal wolf bites (and, in Rowling’s magical world, the werewolf symptoms that might result).

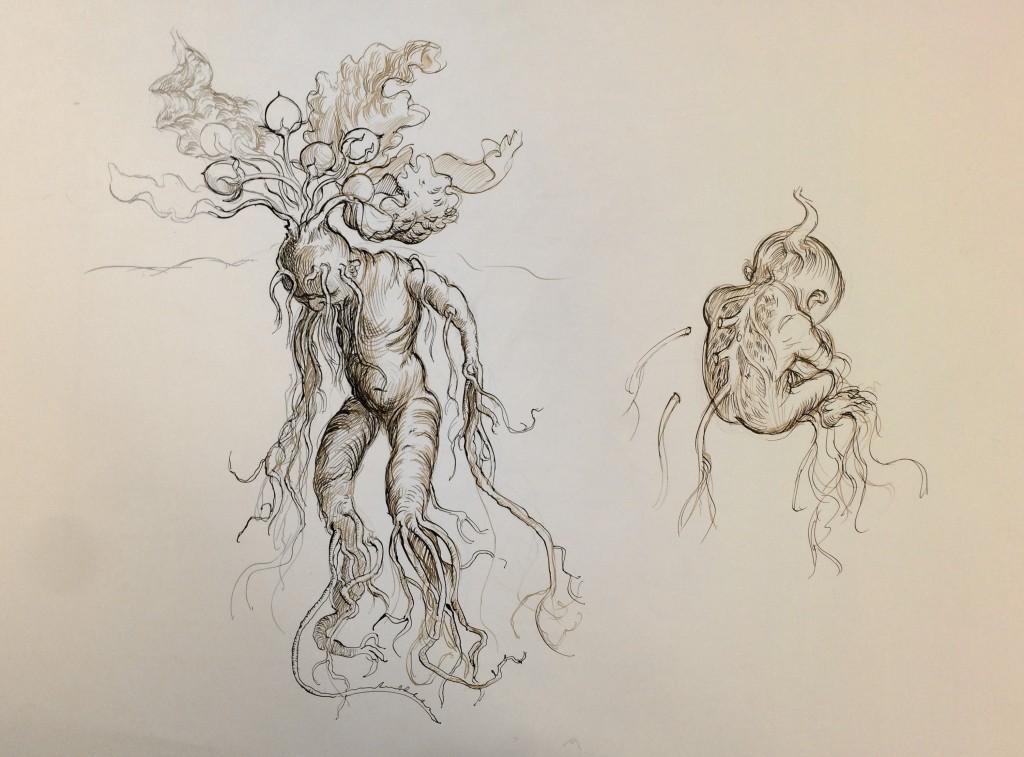

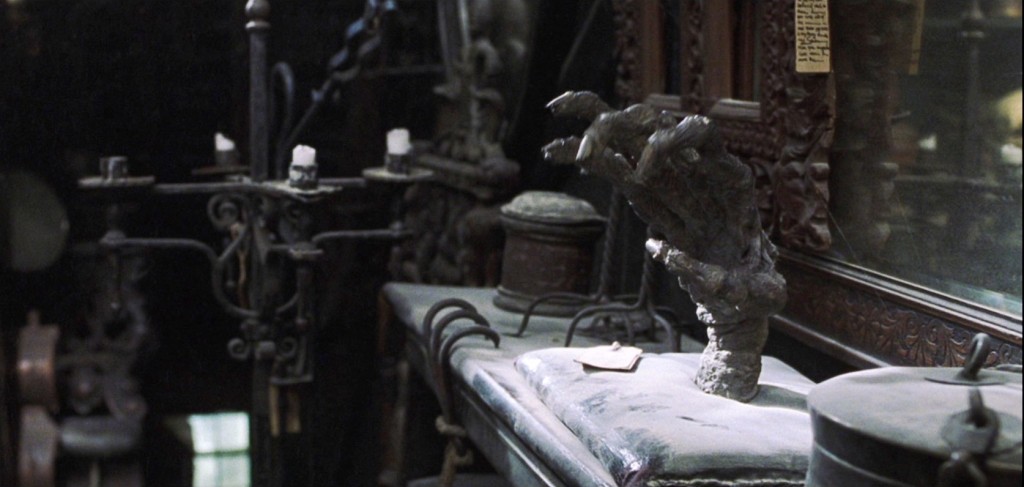

The same is true of mandrakes. The exhibition showcases a strikingly humanoid early modern dried mandrake root, as well as Jim Kay’s beautiful pseudo-botanical illustrations of baby mandrakes:

(© Bloomsbury Publishing pls)

The belief that the mandrake root looked like the whole body meant that – according to the doctrine of signatures – it could cure any part of the body (a ‘panacea’). This belief maps neatly onto the magical use of mandrakes in Chamber of Secrets for the Mandrake Restorative Draught, as it overturns Petrification, is indeed a panacea for the whole body.

In the History of Magic documentary, Rowling looks at some early modern illustrations of mandrakes and relishes the botanical name ‘mandragora’ as she reads it. In emphasising this word, Rowling reminds the viewer of Hermione’s description of it: ‘Mandrake, or Mandragora, is a powerful restorative… it is used to return people who have been transfigured or cursed, to their original state’ (Chamber, Chap 6).

It is very unusual for botanical names to appear in Harry Potter – Rowling tends to me more taken with more memorable, traditional English names ‘Flaxweed, Toadflax, Fleawort, Goutwort, Gromel, knot-grass, Mugwort’ – and I think the name Mandragora might appear because it is a clue that points towards something else. For Mandragora is in fact the source for another object that turns up in Chamber: the Hand of Glory.

I love the ‘humanising’ mandrake jokes in Chamber: Professor Sprout fussing over getting them into woolly socks and scarves when it snows and her observation that they be mature when they make a move on each other’s pots (a joke that draws on Rowling’s knowledge of plant lore: mandrakes were indeed believed to come in male and female forms). Sprout’s enthusiasm is heart-warming and unlike many Muggle parents she even relishes the onset of puberty: she is pleased when the mandrakes become moody and secretive and delighted when they throw a raucous party. But there is a macabre frisson underlying Professor Sprout’s maternal satisfaction in the flourishing of her mandrakes; a unsettling continuity with those evil fairy tale witches who fatten up children on gingerbread. For Sprout is nurturing her mandrakes to maturity only in order to cut them up and stew them in a potion.

Rowling, of course, relishes the macabre. One of the clearest examples of this is the Hand of Glory which Harry comes across in Borgin and Burkes. This is the chopped off hand of a hanged man into which you can ‘insert a candle and it gives light only to the holder’ (Chamber, Chap 4). Rowling has twice noted in interview her perverse enthusiasm for this traditional concept:

“…there is an object in the second book, which is the Hand of Glory. This is very macabre, but people used to believe in Europe that, if you cut off the hand of a hanged man, it would make a perpetual torch that gave light only to the holder, which is a creepy, you know – but a wonderful idea. So I used that. That’s a very ancient idea. I didn’t invent the Hand of Glory.”

However, according to some medieval plant lore the mandrake, too, could ‘shine at night, like a lamp’ (from Dendle’s Plants in the Early Medieval Cosmos: Herbs, Divine Potency, and the ‘Scala natura’) and it is the ultimate source of the idea of the Hand of Glory. The English name (as Rowling, with her excellent French, no doubt knows) is a translation of ‘main de gloire’ – a corruption of the medieval Latin ‘Mandrogora.’ Originally the Hand of Glory was not a real hand at all, but a ‘a mandrake root shaped like a hand. The term is a translation of French main de gloire, which is a popular corruption of mandegore, mandragora, mandrake.

There is a macabre but satisfying circularity in the way in which the humanoid mandrakes which Sprout has mothered so enthusiastically, and yet will chop up, are the original source for the chopped off Hand of Glory ‘main de gloire’ or ‘mandragora’…

That’s the end of the first of FIVE parts to this in-depth analysis of plant lore in Harry Potter, in celebration of the New York opening of Harry Potter: A History of Magic! Book your tickets to the exhibition at the New York Historical Society website, read more about the documentary (which is now available on DVD), the official book of the exhibition, and Dr Groves’ previous analysis of the exhibition in London for more exciting insights. Also be sure to check out Dr Groves’ book, Literary Allusion In Harry Potter, and follow her on Twitter!

Let us know your thoughts – have you been to the exhibition? Were you surprised by the connections between Mandrakes and the Hand of Glory? Were any Hufflepuffs out there a little creeped out by their Head of House when discussing Professor Sprout raising the mandrakes to stew? Comment below, or discuss with us via Twitter, Facebook or Instagram!