“Harry Potter: A History of Magic” and Plant Lore, Part 3: Plants and J.K. Rowling’s Cratylic naming

Oct 17, 2018

Exclusives, Fans, J.K. Rowling, News

Tomorrow evening, Leaky’s webmistress Melissa Anelli will host a talk on the Potter phenomena, titled “Magic for Muggles”, at the newly opened Harry Potter: A History of Magic exhibition at the New York Historical Society. The New York City exhibition differs from its London debut in many ways, for example, hosting Brian Selznick’s 20th anniversary illustrations for Scholastic and Mary Grandpré’s cover art. Of course, it gives the same profound revelations of the mythology, lore and history which inspired J.K. Rowling when writing Harry Potter, and ways in which we can see magic throughout Muggle history.

Happy Monday! Reminder that THIS THURSDAY I’m speaking about the Potter phenomenon at @NYHistory — some tickets are still available! I hope to see you there! https://t.co/eICeTe205q

— Melis-scare Boonelli👻🎃👻🎃 (@melissaanelli) October 15, 2018

Dr Beatrice Groves – publisher of Literary Allusion In Harry Potter and Potter-expert who previously analysed the exhibition when it appeared in London – is taking us through the exhibition through the lens of plant lore, looking into how J.K. Rowling’s world of plants, potions and magical lore was inspired by muggle herbologists. Continuing to look at Rowling’s use of Culpeper’s Complete Herbal and the Doctrine of Signatures, Groves takes a look at the names of the Potter series, exploring how cratylic naming (whereby the name of a person fits their nature) is used by J.K. Rowling throughout the series, particularly in her use of plant-based names, inspired by Culpeper’s guide to the world of greenery.

Part 1: J.K. Rowling and Culpeper’s Complete Herbal | Part 2: Bubotuber Pus and the Doctrine of Signatures | Part 3: Plants and J.K. Rowling’s Cratylic naming | Part 4 (coming 18th October!) | Part 5: (coming 20th October!)

Part 3: Plants and Cratylic naming

Harry Potter’s names are an exuberantly joyful, as well as highly informative, part of its imagined world. Naming is an important literary skill for ‘when we meet a name that just seems right… a peculiar magic happens that is related to aesthetic pleasure: the instance both modifies and validates the invisible conventions that we didn’t know we knew.’ A name that fits the nature of the person who is named is called a cratylic name, and almost every name in Harry Potter works this way. It is a style of naming which encourages readers in a bit of sleuthing: Percy Weasley’s middle name (Ignatius), for example, suggests that, like Ignatius Loyola – who underwent a famous conversion – he might switch sides.

Cratylic names derive from Plato’s dialogue Cratylus in which the character Cratylus believes in the divine origin of names. He thinks the form of a name – its sound, for example – will ‘fit’ the thing named, and hence that names are a divinely inspired guide to reality (for more details on this, see Literary Allusion in Harry Potter, Chapter 2).The doctrine of signatures, therefore, is a kind of physical version of cratylic naming. Both cratylic names and the doctrine of signatures argue that God has inscribed the inner natures of things on their outward forms and in both the truest nature of things is rendered legible. There is something particularly satisfying, therefore, when Rowling creates cratylic names from plants, and this blog will look at three of my favourites:

Poppy Pomfrey

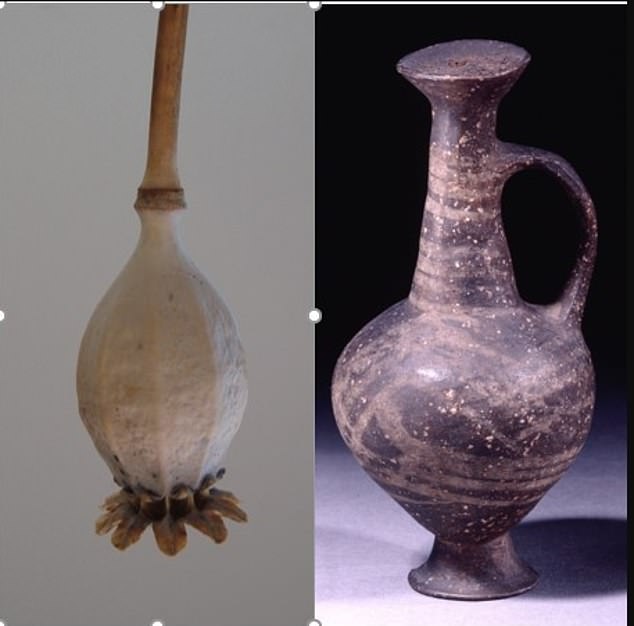

Madam Pomfrey’s name, suitably for someone so skilled in healing magic, is made up of no fewer than three medicinal plants. Her Christian name – Poppy – is the perfect name for someone who is obsessed with getting her patients to sleep: ‘you need rest’; ‘This boy needs rest… Out! OUT!’; ‘Headmaster!’ spluttered Madam Pomfrey. ‘They need treatment, they need rest’ (Philospher’s Stone, Chp 17; Chamber, Chp 10; Azkaban, Chp 21). The Latin name of the opium poppy (Papaver sominiferum) points to their sleep inducing qualities (think of what fields of them do to Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz) and the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius used to opium to help him sleep (as well, in large quantities of honey, to elevate his mood at the start of the day), and opium has long been traded throughout history – take a look at a newly found link between Bronze Age jugs and opium trade (suspected due to their inverted poppy head shape) here.

Poppies are, famously, the source of opium, but while we think of opiates primarily as pain-relieving, Culpeper stresses how good they are at procuring rest:

“The garden Poppy heads with seeds made into a syrup, is frequently, and to good effect used to procure rest, and sleep… the empty shells, or poppy heads, are usually boiled in water, and given to procure rest and sleep: so doth the leaves in the same manner… It is generally used in treacle and mithridate, and in all other medicines that are made to procure rest and sleep.”

So while Poppy Pomfrey’s Christian name relates to the pain-relieving aspects of the juice of opium poppies, I think it is primarily a nod to Madam’s Pomfrey’s prevailing health obsession: ‘this boy needs rest.’

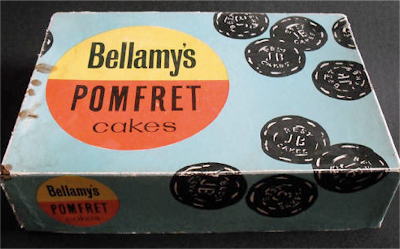

Madam Pomfrey’s surname is a ‘portmanteau’ name: a name in which, as Lewis Carrol put it, has ‘two meanings packed up into one word.’ Rowling loves portmanteau names (‘Azkaban,’ for example, combines the island prison Alcatraz and the Hebrew word for the depths of hell ‘Abaddon’) and ‘Pomfrey’ is a portmanteau of Pomfret cakes (traditional medicinal sweets made from liquorice root) and the medicinal herb Comfrey.

Pomfret cakes were first marketed by an apothecary from Pontefract, but they were based on the much older use of liquorice for throat problems. Culpepper includes a recipe a lozenge (or what he charmingly calls ‘a fine licking medicine’) under his entry for liquorice: ‘the juice of Liquorice… distilled in Rose-water, with some Gum Tragacanth, is a fine licking medicine for hoarseness.’ Liquorice was big business in Yorkshire by the mid eighteenth century (there were nearly fifty liquorice growers in Pontefract alone) and when a local apothecary had the bright idea of adding sugar to this traditional remedy, commercial liquorice sweets – ‘cakes from Pontefract’ or ‘Pomfret cakes’ – were born.

The link of Madam Pomfrey’s name with the sweet Pomfret cakes fits with her enthusiasm for the pleasanter medicines of the wizarding world (in particular, chocolate) but the other source of her name – Comfrey – speaks to another of her specialities.

Culpeper notes how very useful Comfrey (illustrated above) is in all sorts of ways – ‘it contains very great virtues… The root boiled in water or wine, and the decoction drank, helps all inward hurts, bruises, wounds, and ulcer of the lungs’ – but its particular virtue is in mending bones: ‘the roots being outwardly applied, help fresh wounds or cuts immediately, being bruised and laid thereto; and is special good for ruptures and broken bones; yea, it is said to be so powerful to consolidate and knit together, that if they be boiled with dissevered pieces of flesh in a pot, it will join them together again.’ That final detail makes one wonder if Wormtail might have dropped some Comfrey in the Voldemort’s cauldron, but more positively Comfrey’s skill in knitting together broken bones echoes Madam Pomfrey’s known prowess in this department: ‘I can mend bones in a second’ (Chamber, Chp 5).

Pomona Sprout

Pomona Sprout’s first name comes not from a plant but from the Roman goddess Pomona (from the Latin pomum ‘fruit’ in particular ‘orchard fruit’). In a nice touch, Pomona is not connected so much with the fruit harvest, but with the flourishing of the trees themselves – her attribute is a pruning knife. Professor Sprout is linked with her mother in Rowling’s mind, because (in a strange coincidence) she was drawing the picture of Professor Sprout (which is on display in the History of Magic exhibition) on December 30th 1990, the night when her mother died.

The motherly nature of Professor Sprout is underlined in Chamber (the novel in which she plays her biggest role) by contrasting her with Harry’s ‘false’ mother, Aunt Petunia: ‘her fingernails would have made Aunt Petunia faint’ (Chap 6). Both of Professor Sprout’s names are all about the flourishing of plants under her care and Rowling has spoken in the documentary accompanying the History of Magic exhibition of how she maternal she finds her: ‘I would say she’s the most maternal… of the four heads of house at Hogwarts.’

Scorpius Malfoy

There might also be a plant name hiding at the end of Deathly Hallows that has not been generally recognised as such. Scorpius Malfoy is generally considered to have been named after the constellation Scorpius (Latin for ‘scorpion’). This makes sense given the fashion among pure-blood families for naming their children after stars (Merope, Sirius, Regulus Arcturus) and constellations (Orion, Cassiopeia, Draco). This pure-blood tradition has dark origins: the most famous character to share his name with a star is Lucifer (whose name means ‘light bearer’). When we meet little Scorpius (whose name sounds so immediately unappealing) the reader naturally assumes he is part of this ‘dark’ tradition and that he will turn out to be a bit poisonous (like a scorpion) and a perfect Slytherin like his father. The plot of Cursed Child (with the hints that he might be the dark cloud threatening Albus) keeps this idea in play, but it turns out that Scorpius is the most lovable character of the play: gentle, self-effacing and loyal. (I wonder if Scorpius, like Harry, chose his house from filial loyalty, while the Sorting Hat was saying ‘Slytherin, really? You’re a Hufflepuff mate’).

Scorpius’s true nature – the friend who is able to cure Albus’s Slytherin side: Albus’s dangerous need to compete with his father’s legacy – is coded in another source for his name: the herb (& plant genus) Scorpius.

In the world of the doctrine of signatures resemblance idenicates cure – Paracelsus’s ides of similia similibus curantur (‘like cures like’). Something that looks like a Scorpion is not poisonous like a Scorpion but can protect you from that poison. The Greek physician Dioscorides (an important source for Culpeper) wrote that ‘the Herb Scorpius resembles the tail of the Scorpion, and is good against his biting.’[7] The herbal source of Scorpius name expresses the way that he will protect against Albus’s overly Slytherin tendencies. He is not destined to become the Scorpion King but is instead the heroic saviour of Hogwarts from a pure Slytherin future where all the house flags are snakes.

What are your thoughts on these new insights into J.K. Rowling’s laborious process of naming characters? Do you think you full appreciated the thought that went into each name when you first read the series? Let us know your thoughts in the in the comments, or via Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.

Book your tickets to the exhibition at the New York Historical Society website, read more about the documentary (which is now available on DVD), the official book of the exhibition, and Dr Groves’ previous analysis of the exhibition in London for more exciting insights. Also be sure to check out Dr Groves’ book, Literary Allusion In Harry Potter, and follow her on Twitter.

Look out for Part 4 tomorrow!

References:

[1] Colin Burrow, ‘I, Lowborn Cur,’ London Review of Books 34.22 (22 Nov 2012): 15-17.

[2] For more on Cratylic naming see: Groves, Literary Allusion in Harry Potter, Chap 2; Beatrice Groves, ‘What’s in a name? Cratylic naming in Harry Potter and Dickens’ English Review 28.3 (2018): 2-6.

[3] John Scarborough, ‘The Opium poppy in Hellenistic and Roman medicine,’ in Drugs and Narcotics in History, ed. Roy Porter and Mikuláš Teich (CUP, 1995), pp.17-8.

[4] For more on portmanteau names in Rowling see: Groves, Literary Allusion in Harry Potter, Chap 2.

[5] Kate Hopkins, Sweet Tooth: the Bittersweet History of Candy (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2012), p.137.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pomona_(mythology)

[7] Bradley C. Bennett, ‘Doctrine of Signatures: An Explanation of Medicinal Plant Discovery or Dissemination of Knowledge?’ Economic Botany, 61.3 (2007): 246-55.