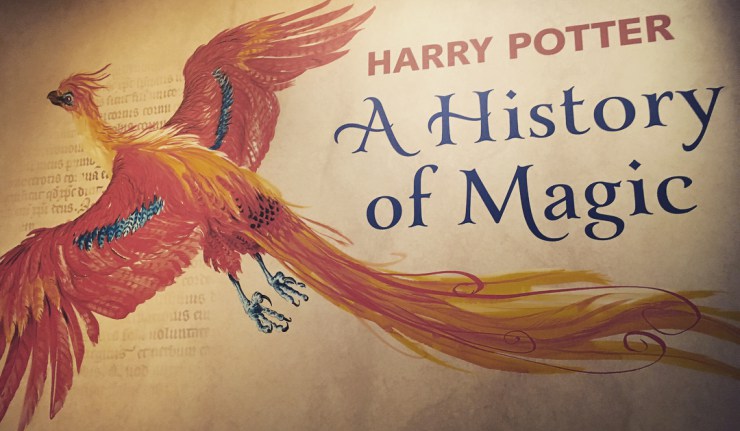

A Potter Expert’s Account of the ‘Harry Potter: A History of Magic’ British Library Exhibition

Feb 05, 2018

Art, Bloomsbury, Events, Fans, J.K. Rowling, Jim Kay, News, Publishers, Warner Bros.

Dr Beatrice Groves – Research Fellow in Renaissance English at the University of Oxford – possesses all necessary traits of what one might call a complete and utter Potter expert. Focusing her research on early modern literature and drama (Shakespeare in particular), Groves recently published Literary Allusion In Harry Potter: a book exploring J.K. Rowling’s references to famous Western literary canon throughout the Harry Potter series.

We’re hugely excited to introduce Groves as our guest writer for this exciting piece: an in-depth account (complete with Potter quotes, literary and artistic references, past J.K. Rowling interviews and more!) of the Harry Potter: A History of Magic exhibition, currently residing at The British Library until February 28th (tickets have sold out!) and moving to New York this Autumn.

Without further ado, allow us to present Groves’s commentary on the exhibit – be sure to let us know your thoughts and reflections, and if you’ve visited the exhibit we’d love to know what parts were your favourite!

Harry Potter: A History of Magic, the British Library Exhibition

– Dr Beatrice Groves

This exhibition, marking 20 years since the birth of Harry Potter, centres on eight rooms corresponding to subjects taught at Hogwarts. The exhibits comprise of three main strands: manuscripts, books and artefacts detailing the history of magic; original paintings by Jim Kay (celebrating the new, illustrated Harry Potter editions) and either rarely seen or never before displayed Harry Potter manuscripts, drafts and jottings. I visited the British Library last month and many of the exhibits, as well as being fascinating in their own right, shone fresh light on the Potterverse.

The history of Smelly Nelly, for example, a 20th century witch who believed that strong perfumes appealed to the future-divining spirits, provided useful context for Trelawney’s heavily-scented room; while the delicate pink cup which had been specifically designed for tasseography (the reading of tea-leaves) formed a tempting connection with Trelawney’s fondness for her pink cups…

It was likewise interesting to note that Rowling’s sketch of Hogwarts, like her earlier-released sketch (available on the Azkaban DVD extras), marks the landscape of Hogwarts as explicitly Scottish. In both sketches Rowling chooses to identify the school’s lake as a loch. It is tantalising that this identification (which would have prevented even the most casual reader from missing Hogwarts’s Scottish location) never made it into the books. Perhaps the parallel between the giant squid and Nessie would have just seemed too pointed if the Great Lake had been named the Grand Loch?

The exhibition’s displays generate enriching connections with Harry Potter by encouraging the viewer to think about the series from a fresh angle. Below are some of the ideas which occurred to me on viewing the exhibits – and I’d love to hear below of any that you spotted!

Magical books, manuscripts and artefacts

One of my favourite exhibits were the Ethiopian amulet scrolls in the Defence Against the Dark Arts room. In Harry Potter maternal love – ‘the power that you give someone by loving them’ – has a talismanic power (connected, as Rowling has explained, to her own experience of grieving for her mother). One of the odd aspects of this power in the series is the specificity of its location: ‘it is in your very skin’ (Philosopher’s Stone, Chap 17). This emphasis on maternally-charmed skin is recalled when Hagrid duels a Death Eater at the end of Half-Blood Prince and Harry notes how his life is saved by the toughened skin his mother has passed on to him. It was fascinating, therefore, to learn that Ethiopian amulet scrolls – charms rolled in scrolls and often worn close to the body to keep the wearer safe – are known (because they are written on parchment) as ‘ya branna Ketnab’: written on skin.

The Care of Magical Creatures room is full of beautifully illustrated books – among them a copy of Ludovico Ariosto’s sixteenth century epic poem Orlando Furioso which carries a hippogriff on its frontispiece. Hippogriffs, a legendary offspring of griffins and horses, were first so-named by Ariosto and, suitably enough, in his poem the hippogriff makes its first appearance being ridden by a wizard. Another illuminated book in this room is Ulise Aldrovandi’s Serpentum et Draconum Historiae (1640) which describes in all seriousness how some species of dragon are distinguishable by the ridges on their back – irresistibly reminiscent of Rowling’s Norwegian Ridgeback.

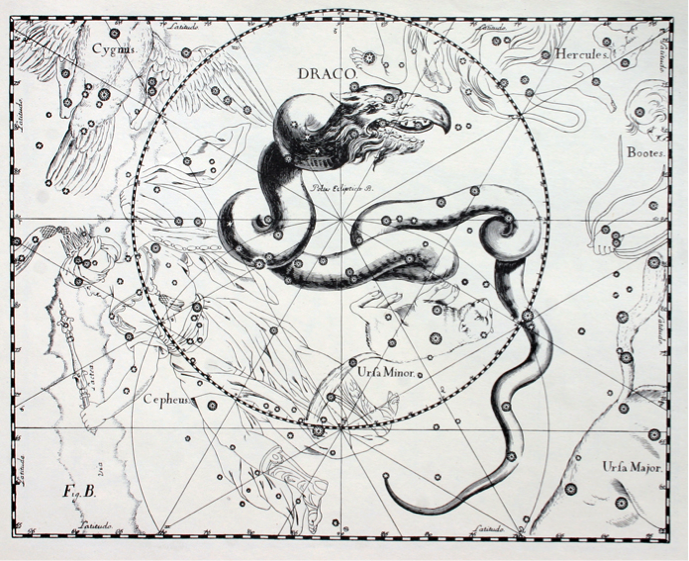

This book’s title – Serpentum et Draconum Historiae – illustrates the way that the history of serpents and dragons are intertwined. The stunning interactive terrestrial globe (which forms the central exhibit of the Astronomy room) notes that Draco Malfoy is named after the constellation ‘Draco’ (the dragon). (Earlier in the exhibition there is an eighteenth century apothecary jar marked, delightfully, ‘Sang. Draco:’ dragon’s blood.) In Greek and Roman myth, however, ‘dragons’ are in more like monstrous snakes that the dragons of modern imagining – and the twists and turns of the Draco constellation make this snakiness clear:

The Draco constellation is probably named not after a ‘dragon’ as such, but rather the serpent who guarded the golden apples of the Garden of the Hesperides. This serpent, draped round an apple tree in a mythic garden, is reminiscent of rather more infamous snake – who also took to twining itself round an apple tree in an idyllic garden.

The well-known derivation of Draco Malfoy’s name from this constellation is, of course, part of the pure-blood enthusiasm for star-based names: Merope, Sirius, Regulus Arcturus, Orion, Cassiopeia, Scorpius etc. It is a fashion that can be traced back to the first bearer of a star-based name: Lucifer, the morning star. Lucius’s name directly recalls Lucifer’s – and possibly his son’s name, also, has a rather stronger Satanic resonance than has been previously noted. The Draco constellation, snaking its way through the sky, is named after a serpent guarding apples in a mythic garden. A snake whose story bears strikingly Satanic overtones. (It also makes sense that the arch-Slytherin Draco – put in that house the moment the Sorting Hat approaches his head – should be named after a serpent.)

One of the objects I found most illuminating (suitably enough, they were in the Divination Room) were a set of eighteenth-century divination cards; probably the first set of playing cards specifically designed for cartomancy.

Modern ‘tarot’ cards have a number of well-known images, such as The Fool, Wheel of Fortune, Death and The Lovers (the latter, in particular, deeply familiar to anyone who grow up in the 1980s when ‘holiday TV’ meant yet another showing of Live and Let Die….). The influence of two tarot images are legible in Harry Potter. The first is The Hanged Man – an enigmatic image which, of course, gives its name to the pub in Little Hangleton.

The other is The Tower, which turns up in one of the decks Trelawney uses for cartomancy:

The image above (from a classic and popular tarot design) is likely to be the image Rowling imagined for Trelawney’s deck as it is a lightening-struck tower, as Trelawney’s is. It is noticeable (as is not mentioned in Half-Blood Prince) that this card also shows figures falling from the tower.

As these references indicate, Rowling researched cartomancy for Harry Potter. In an early interview (in 1999) she noted that as a result of her research ‘I know a lot about foretelling the future without, I have to say, believing in it.’

She also brought along to the interview some of her research books, including one of the literally hundreds of publications entitled Fortune Telling by Cards. (It is not clear which version she is using, but many of these works are written by authors who rejoice in such Potteresque names as Ida Prangley, Professor Foli, James Cumberbirch and Sepharial). These researches suggest that she could have come across images of reputedly the first set of cartomancy cards – now on display in the British Library. These do not bear the familiar tarot images but are inscribed instead with the names of famous seers, astrologers or magicians. The names of famous magicians (such as Merlin, Dr Faustus or Dr Dee) on divination cards presumably gave their users faith in their ability to foretell the future. But it also means is that these cards have a tantalising connection with another set of cards within Harry Potter: Chocolate Frog cards.

Rowling has based her collectable Chocolate Frog cards on the cigarette cards that were (however odd this may seem to us now!) the childhood collecting craze of the late Victorian era onwards. From the 1870s collectable sets of cards – carrying portraits of film or sporting stars on the front, and a potted biography on the back – came free with cigarette packs. These cigarette cards shared with Chocolate Frog cards in the visual excitement of their pictures. Harry is transfixed when, with his first Chocolate Frog card, he first discovers that wizarding pictures move and for a nineteenth-century child the visual pleasures of these cigarette cards could carry something of the same excitement. As one early collector noted, they came at a time ‘with no newsreels… no picture newspapers. A good cigarette picture was no mere plaything for a boy. It was life.’

While cigarette cards – collectable, free with a purchase and carrying a short biography of their subject – are clearly the primary Muggle-parallel for Chocolate Frog cards, I did wonder on seeing these early divination cards whether they may also have inspired Rowling. Unlike cigarette cards, but exactly like Chocolate Frog cards, these early divination cards carry the names of witches and wizards. And in some cases, they refer to precisely the same wizards who appear on Chocolate Frog cards.

The first two Chocolate Frog card wizards mentioned in Harry Potter are Ptolemy and Agrippa. Both of these are historical figures – Claudius Ptolemy was a 2nd century Greco-Roman Astronomer and Astrologer, while Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa was imprisoned in the a sixteenth century for his occult writings. (Incidentally, none of the other Famous Witches and Wizards we hear of within the series are historical figures and it may be intentional that it is only these real/Muggle ‘wizards’ who are evading Ron’s collection!) Ptolemy and Agrippa, as well as Merlin (another Chocolate Frog card favourite), are likewise found on the divination cards in the British Library exhibition. This possible cartomancy connection is appealing as it underlines the way that the Chocolate Frog card Harry unwraps on the Hogwarts Express acts as an accurate guide to the future.

As Rowling notes in the BBC 2 Harry Potter: A History of Magic documentary that accompanied the opening of the exhibition: ‘I have a lot of fun with Divination in the Potter books because I make it quite clear that you get lucky once in a million times’ (and then, with emphasis) ‘free will is the abiding principle of the Potter books not prophecy.’ Divination does indeed have a bad press in Harry Potter but, as every fan knows, Rowling has her Divination cake and eats it. She makes comic capital out of Trelawney’s fraudulence (‘Tripe, Sybill?’ [Azkaban, Chap 11]) then has pretty much everything she says come true in one way or another. (One example of divination ‘working’ within the series can be deciphered from another Divination exhibit: Tea Cup Reading: How to Tell Fortunes by Tea Leaves (c.1920). This widely available book, written ‘by a Highland Seer,’ explains that seeing a dog in the tea leaves signifies not death – as Trelawney believes when she sees the ‘Grim’ – but a faithful friend. Trelawney may be wrong, but the tea leaves are not. Tasseography – in keeping with the games Rowling plays throughout Potter – sees through Sirius’s disguise and reveals him as the faithful friend he really is).

The only two times we see Trelawney reading the cards, likewise, cartomancy is unerringly accurate. She is unknowingly precisely on the money when she reads Harry’s cards (as he crouches, hidden, in front of her) as ‘a dark young man, possibly troubled, one who dislikes the questioner’ (Half-Blood Prince, Chap 10). And Dumbledore dismisses Trelawney’s dire warnings about the lightening-struck tower being on the cards not because he thinks she is simply wittering on about calamity, but precisely because he knows death is coming for him.

The only Chocolate Frog card we ever read in Harry Potter, likewise, tells the truth about the future. Dumbledore’s potted biography on his Chocolate Frog card tells of his alchemical achievements with Nicholas Flamel which are, of course, a direct hint about what will happen in the rest of Philosopher’s Stone. Less obviously, although now well-known, its recounting of his defeat of Grindelwald in 1945 is also a hint. It creates a resonance between the events in the magical and Muggle worlds, an idea that resurfaces throughout the series. By giving the date of the allies’ defeat of Nazi Germany as the defeat of Grindelwald, it also connects him in particular (and his pure-blood ideology, in general) with fascism in a way that will be strongly marked when he returns in Deathly Hallows. In the final novel Grindelwald’s mark – like the Nazi swastika – co-opts a pre-existing sign (the swastika is an ancient religious symbol common to Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism) and irrecoverably taints it. Grindelwald’s slogan, likewise, ‘For the Greater Good’ is ‘carved over the entrance to Nurmengard’ (Deathly Hallows, Chap 18) in a reference to the infamous words written over the entrance to Auschwitz: ‘Arbeit macht frei’ (‘Work makes you free’). The reference to 1945 on Dumbeldore’s Chocolate Frog card gestures towards some of Harry Potter’s larger ambitions, as yet unsuspected by the reader. When Grindelwald – mentioned only in the first and last novels – returns, it marks one of the circles which underlie the ring structure of the entire series.

The Chocolate Frog cards, like Trelawney’s deck of cards, tells the reader about the future – just as their connection with the first cartomancy cards suggest they might.

Jim Kay’s portraits, Holbein and allusive objects

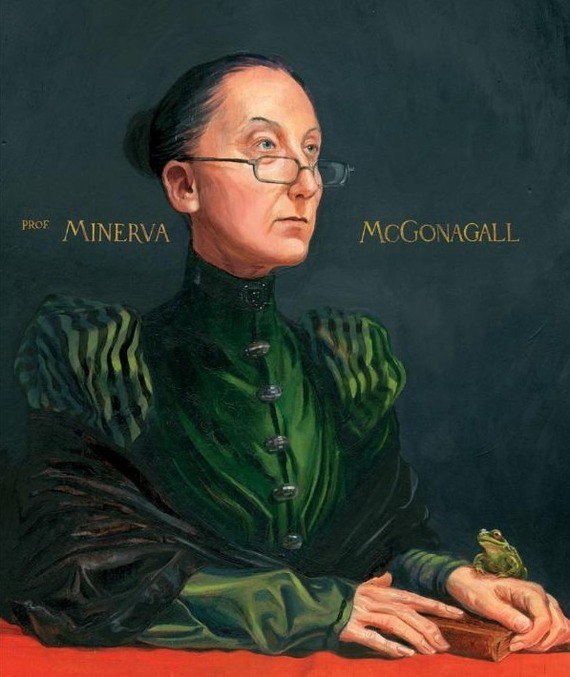

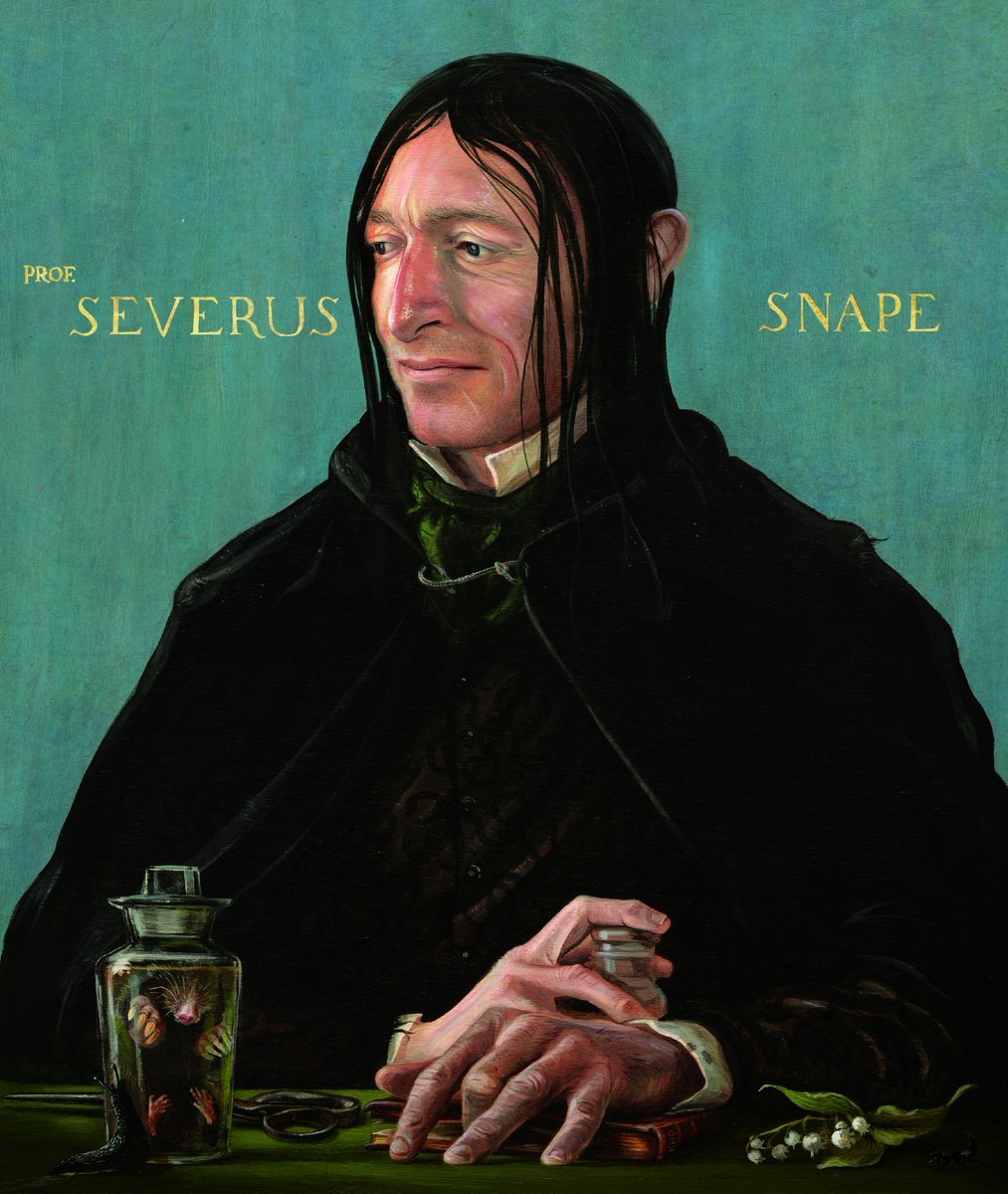

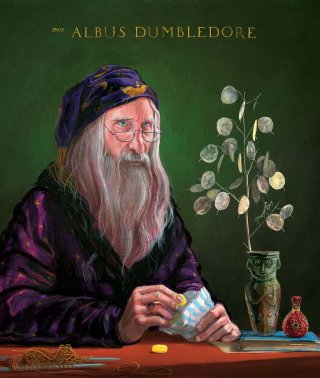

Jim Kay’s artwork is a major part of the visual pleasure of the exhibition. My favourite were his portraits, in particular those of Lupin, Dumbledore, McGonagall and Snape. The latter three portraits – richly coloured studies which portray their subjects half-length, seated at a table and gazing into the middle distance – are strongly influenced by the one of the greatest portrait artists: Hans Holbein the younger. Take, for example, the way that Kay’s portrait of McGonagall (above) contrasts the soft silk of her richly textured sleeves with the hard gaze of her keenly intelligent face. Superb sleeves are common in Holbein, where they display both the wealth of the sitter and the skill of the painter. Kay’s McGonagall echoes Holbein’s Thomas More where the lush velvet of arguably the most covetable set of sleeves ever painted create a depth of contrast for the steely intellect of More’s gaze:

Holbein’s portraits combine near-photographic realism – with clothes that look soft to the touch and facial expressions that make personalities palpable across the divide of half a millennia – with self-evident markers of artificiality. One of example of this is the prominent inscription of the canvases with information identifying the sitter (giving their age, name or motto) in gold capitals:

This practice is referenced by Kay as he writes Dumbledore’s, Snape’s and McGonagall’s names in gold capitals directly onto their backdrop. (In the case of McGonagall and Snape’s portraits this lettering is also in precisely the same position as Holbein’s, bisected by the sitter’s head.) This clear visual echo of Holbein draws attention, like his lettering, to the portrait’s artificiality: forcing the viewer to note that the painter is not simply recording what he sees. These portraits, by explicitly drawing attention to their artificiality in this way, gesture, likewise, to the idea that other aspects of the painting may be more than simple, realistic depictions. (The most famous and dramatic example of this in Holbein’s art is the vast, distorted skull at the bottom of The Ambassadors which draws attention to the symbolic meaning of every object in the scene.) Kay’s portraits allude to Holbein’s in their composition, use of colour and textural detail but also, most tellingly, in the symbolic nature of the objects that surround the sitter. The eloquent objects in Kay’s portraits are a homage to both Holbein’s and Rowling’s allusive style, where detail always carries meaning.

Perched on top of McGonagall’s hand, for example, is a toad, recalling a number of enigmatic animals which appear with sitters in Holbein’s portraits – in particular the squirrel perched on the wrist of A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling:

The squirrel and starling in this painting have been read by art historians as coded references to the sitter’s name: could she be Anne Lovell? ‘Squirrel’ sounds a bit like Lovell and ‘starling’ likewise puns on their home in East Harling. While this does not sound wildly convincing (!), sixteenth-century aristocrats were fond of a type of heraldry called ‘canting’ heraldry which punned on their names – and the Lovell family did indeed include squirrels on their coat of arms. The animals in Anne Lovell’s portrait, therefore, are probably clues to her identity as the toad in McGonagall’s portrait, likewise, functions as a code for identity as a witch and, more specifically, her abilities as an Animagus.

Another object common to both Kay and Holbein’s portraits are scissors. Scissors appear frequently in Holbein’s portraits and while sometimes they may be no more than markers of the sitter’s trade, at others, they appear to carry greater symbolic emphasis. Such as the pair, for example, that lie at the elbow of the enigmatic, arch-politician Thomas Cromwell:

This portrait was commissioned c.1532-3 when Cromwell had just become Henry VIII’s chief minister, and the scissors are not only part of the practical accoutrements of statecraft but also hint at his power. Scissors can be dangerous but they are also a finely tuned instrument in which both halves work together to achieve an end. Their inclusion in Cromwell’s portrait suggests both his mental sharpness and the smooth running of the state while he is chief minister.

Kay’s portrait of Snape (above) surrounds its subject with symbolic objects including, like Holbein’s Cromwell, a pair of scissors. The curators of the exhibition note the connection of these scissors with Snape’s Sectumsempra spell, but they also have a more symbolic link with Snape’s status as a double-agent. The two halves of his identity work together to cut through Voldemort’s schemes.

The Holbein portrait which Snape’s most closely recalls, however, is his 1523 portrait of Erasmus:

While Erasmus’s face is composed in equal parts of beatific serenity and a self-conscious satisfaction in a job well done and Snape’s expression is described in the exhibition catalogue as ‘look[ing] listlessly down at something out of sight, with a half sneer contorting one side of his face,’(p42) nonetheless if you compare the portraits the facial similarities (the set of the mouth, with deeply marked lines on the left side, the three-quarter presentation and slightly hooded eyes) are striking. The relationship between the two portraits is a sign that Snape’s expression is more enigmatic than the catalogue allows, but it is also a marker of Snape’s connections with the book on which his hands likewise rest.

Books are prominent in all three of Kay’s portraits, as they are in so many Holbeins, perhaps most strikingly in Erasmus’s portrait where his hands, like Snape’s, rest proprietorially on a book. The inscription on Erasmus’s book presumably references the version of the New Testament he had produced in 1516. It reads ‘the Herculean labours of Erasmus of Rotterdam’, a reference to Erasmus’s own remark: ‘If any human labours deserve to be called Herculean, it is certainly the work of those who are striving to restore the great works of ancient literature.’ While it is difficult to see this in reproductions, Snape’s book, too, is inscribed with ‘HBP’ prominently marked on the spine. This book, therefore, is the Half-Blood Prince’s copy of Libatius Borage’s Advanced Potion-Making. Just as Erasmus proudly displays a book which he believes he has transformed (through his parallel Latin and Greek texts) for his readers, so Snape is confident that his illuminating annotations transform the worth of Borage’s textbook.

The objects in Snape’s portrait are all symbolic: the bottled mole (or Niffler?) expresses his undercover work, the lily of the valley his love for Lily and while his left-hand rests on the Half-Blood Prince’s textbook, with his right hand he holds down the stopper of a flask. This firmly stoppered flask reminds the viewer of Snape’s boast in Harry’s first Potions lesson that he can stopper death (a crucial clue to his later actions). The flask expresses Snape’s skill at Potions and, slightly surprisingly, there is a flask, likewise, lurking in Holbein’s portrait of Erasmus. Flasks, like books, are objects typically found in medieval portraits of scholars and presumably there is an alchemical aspect to this tradition. Due to importance of alchemy in the history of learning it appears that flasks, like books, remained visual markers for ‘scholar’ in artistic depictions beyond the time that the scholar himself was actually a practising alchemist. Dumbledore, of course, is a practising alchemist and so Jim Kay has quite naturally included a flask in his portrait gesturing both to his alchemical researches into the Elixir of Life, and into dragon’s blood.

Beside both Dumbledore and Snape there are not only flasks and books but also flowers. Harry Potter. as is well known, uses the symbolic language of flowers: alongside the evocatively named sisters Lily and Petunia (the latter represents both anger and resentment) there is the persuasive fan theory that Snape’s first words to Harry about asphodel and bitterest wormwood express regret for Lily’s death. Holbein, too, uses the language of flowers – such as those in this portrait of Georg Gisze:

The flowers in Gisze’s portrait are carnations (symbolic of betrothal), wallflowers (symbolic of the Crucifixion), medicinal hyssop and Rosemary (symbolic, as we know from Hamlet, of remembrance). The message of the flowers is evocative, but opaque: is Holbein signifying Gisze’s piety? Expressing his love for a woman from whom he is far away? Rejoicing in his health? Or some combination of all these messages? The language of flowers in Kay’s Dumbledore’s portrait – branch of the translucent seed-heads of Lunaria annua, better known as ‘honesty’ – likewise carry a complex signification. While Snape’s lily of the valley has an obvious meaning, Dumbledore’s ‘honesty’ is a more multifaceted. There is a subtle link with his name – probably the most common variant of honesty is alba or albiflora ‘white-flowered honesty,’ reminiscent of Albus’s Christian name. Along with honesty’s Latin name ‘Lunaria’ (moon-like – referring to its round, silver seedpods) this stresses the symbolic silver/white aspect of Dumbledore (an important part of the series’ alchemical imagery). Also, however much we may remain on Dumbledore’s side, he has not been straightforwardly ‘honest’ with Harry (or, indeed, with Snape). Kay has placed a preying mantis lurking in the honesty, a visual marker of the less straightforward undertones beneath Dumbledore’s evident goodness.

In all three portraits Kay’s subjects, like Holbein’s, hold something in their hands. Snape and McGonagall’s hands, both clasping a book as a marker of their intelligence, directly reference Holbein’s practice. But with Dumbledore’s portrait Kay wittily inverts the high culture reference by having Dumbledore’s hands take sherbet lemons from an old-fashioned striped sweet bag. These sweets disrupt the serious expectations formed by Kay’s evocative echoing of Holbein, although they still carry the allusive import of Holbein’s more serious objects. The amusingly discordant sherbet lemons mirror the eccentric charm of Dumbledore’s character and form a visual equivalence for the ‘Brian’ that Rowling has wittily inserted among Albus Percival Wulfric Dumbledore’s more obviously august names.

J.K. Rowling’s manuscripts

The highlight of the exhibition (and where most people were queuing on my visit!) were the many Harry Potter drafts and jottings Rowling has generously donated to the exhibition. These are reproduced even more fully in the excellent exhibition catalogue – which is not hampered in the same way by the problem of only being able to display one side of a piece of paper!

A delightful find is that the smells that Hermione gives when she is defining the characteristics of Amortentia are a late addition – written in by Rowling longhand on a typed draft of a passage in Half-Blood Prince which is otherwise substantially as we know it. Describing this Love Potion, as we know, almost causes Hermione – from her habit of answering teachers’ questions correctly – to reveal her feelings for Ron: ‘“it’s supposed to smell differently to each of us, according to what attracts us, and I can smell freshly mown grass and new parchment and –” But she turned slightly pink and did not complete the sentence’ (Half-Blood Prince, Chap 9). (This unspoken third smell, a clue to the love between Hermione and Ron, has been explained by Rowling in interview: ‘I think it was [Ron’s] hair. Every individual has very distinctive-smelling hair, don’t you find?’) It is interesting to see that this hint of Hermione’s feelings for Ron early in Half-Blood Prince is such a late addition – evidence, perhaps, of Rowling’s belief that this aspect of the plot needed accentuating? (Another part of this manuscript shows the effect of editorial intervention as an editor has crossed out a section in which Rowling tried to convey an explanation of why it is so difficult for Harry to get inside the Room of Requirement when Malfoy is in there – something that, this reader, at least, feels is not quite sufficiently accounted for in the finished novel!).

In a draft of Deathly Hallows we see Harry destroying the Hufflepuff Cup Horcrux (which is destroyed by Hermione in the finished novel). This proves that a satisfying detail of the Horcrux quest – that a different person destroys each one – was not part of Rowling’s first conception. The choice to have a different destroyer for each Horcrux is a strength of the finished plot, representing a democratic evolution of traditional quest narratives with their ‘singular’ heroes. One of the results, however, is that Harry does not actually destroy a single Horcrux in the final novel (as he has already, albeit unknowingly, had this moment in the heroic limelight in Chamber). This early draft which, quite naturally, has the hero destroying a Horcrux underlines how striking a decision it was on Rowling’s part to withhold this climactic moment from her central character. And what a good decision is was, too. It is part of the way in which Harry Potter rises to the challenge of having a non-martial hero, a hero who rejects violence. In Azkaban, for example, the expected murderous climax towards which the novel appears to be building is replaced by Harry’s decision to spare the man who betrayed his parents. Harry also remains steadfast in his use of his ‘signature move’ (Deathly Hallows, Chap 5) – his non-violent Disarming spell – when he faces Voldemort in the duels at the end of Goblet and Deathly Hallows. The way in which the final novel is structured around the hunt of Horcruxes, yet has none of these Horcruxes destroyed by the hero, draws attention to the series’ undercutting of traditional, martial heroism.

One of my favourite Potter-jottings in the exhibition is Rowling’s list of teacher’s names (previously revealed on her website). It provides a number of interesting details: such giving another piece of evidence for Rowling’s fascination with the etymology of names, as she notes: ‘Rosmerta “Good purveyor”.’ Rosmerta takes her name with the Celtic goddess of abundance – “‘ro-’ is an intensifying prefix, ‘smert–’ means ‘looking after, providing’” – and her name evokes both her job as a provider of food and drink but also her warm, open nature. One of the most evocative names in this list, however, is one that never made it into the books themselves: Professor Binns’s Christian name, Cuthbert.

‘Cuthbert’ is one of Rowling’s many saints’ names; names that always carry hints about the nature of the characters who bear them. The Sisters of St Hedwig, for example, were established to educate orphan children, conveying the touching way in which Hedwig cares for Harry, not just (as might be expected with a pet) the other way around. Percy Weasley’s middle name (Ignatius) suggests that, like Ignatius Loyola – a saint who underwent a famous conversion – he might switch sides. One of Dumbledore’s middle names comes from a medieval saint (Wulfric of Haselbury) who was famed for his gifts of healing and prophecy. Cuthbert, likewise, is a deeply suitable namesake for Binns.

Cuthbert is an early English saint (c.635-687) who is connected with one of the British Library’s greatest treasures, the Lindisfarne Gospels, which are believed to have been written in his honour. Cuthbert is a major historical figure: the architectural wonder that is Durham Cathedral, for example, was built around Cuthbert’s shrine and the veneration of this northern saint by Alfred the Great (King of Wessex) marked Alfred’s future-defining vision of the new, united nation. A person of such historical significance is an appropriate namesake for a teacher of history. But Cuthbert is also a name that perfectly fits Binns’ nature. Rowling has noted how Binns was based on a university professor whose ‘disconnect with his students was total’ and Cuthbert, too, was famously unenamoured of those who tried to learn from him. Bede’s Life of St Cuthbert may be both literally and metaphorically a hagiography, but even so Bede can’t prevent him from sounding a tad unconvivial:

“At length, as his zeal after perfection grew, he shut himself up in his cell away from the sight of men, and spent his time alone in fasting, watching, and prayer, rarely having communication with any one without, and that through the window, which at first was left open, that he might see and be seen; but, after a time, he shut that also, and opened it only to give his blessing, or for any other purpose of absolute necessity.“

Binns, we can only imagine, would have envied him.

The exhibition Harry Potter: A History of Magic will open at the New-York Historical Society in October 2018. Tickets will be available for purchase to the general public for the New York run of the exhibition starting April 2018. However, members at the New York Historical Society may begin reserving tickets on February 14th – find out more here!

Thanks to Dr Beatrice Groves for her wonderfully insightful account of The British Library’s exhibition! With so many objects on display, each person is sure to take something different from their visit – if you learned of any surprising connections on your journey to the exhibition, please do let us know in the comments!

A summary of Literary Allusion in Harry Potter is as follows:

“Literary Allusion in Harry Potter builds on the world-wide enthusiasm for J. K. Rowling’s series in order to introduce its readers to some of the great works of literature on which Rowling draws. Harry Potter’s narrative techniques are rooted in the western literary tradition and its allusiveness provides insight into Rowling’s fictional world. Each chapter of Literary Allusion in Harry Potter consists of an in-depth discussion of the intersection between Harry Potter and a canonical literary work, such as the plays of Shakespeare, the poetry of Homer, Ovid, the Gawain-poet, Chaucer, Milton and Tennyson, and the novels of Austen, Hardy and Dickens. This approach aims to transform the reader’s understanding of Rowling’s literary achievement as well as to encourage the discovery of works with which they may be less familiar. The aim of this book is to delight Potter fans with a new perspective on their favourite books while harnessing that enthusiasm to increase their wider appreciation of literature.”

If you loved the exhibit and want to find out more about the connections between Western literary canon and J.K. Rowling’s series, you can purchase the book here. Also check out Harry Potter – A History of Magic: The Book of the Exhibition, a ‘once-in-a-lifetime collaboration’ between Bloomsbury, J.K. Rowling and the curators of the British Library.